THE ART OF THE AUCTION

Most people would assume when you put a watch auction catalog together, it’s just a matter of grouping brands or styles until each item has a lot and then print. If only it were so simple, or rather, if you want a successful auction, it takes much more thought. Take for example Aurel Bacs, who has dominated this field at both Christies then Phillips for decades now. If you look at his past catalogues you’ll notice the first lots are usually modern Rolex estimated at well below market value or no reserve. There’s a reason for this. Aurel wants people to be in the room when the auctioneer steps onto the podium, nothing more enticing then the potential for a bargain to get people motivated, then, as always, due to their low reserve that attracts so much interest, the first lots sell very strongly, it sets the whole auction up as buoyant. Take on the other hand November Geneva when Sothebys failed to sell their first lot and just squeezed the second lot under the estimate, sure they had a few good results in the sale, but it made people pay attention that maybe the specialist’s weren’t on the ball with estimates.

Screenshot of Phillips first three lots offered in their November 2023 Geneva auction, the first lot was no reserve. Impressive results vs estimates to set the tone of the auction. This is almost identical every Phillips Geneva auction for a reason. Interestingly, Phillips, Sothebys and Christies all had identical Rolex 116508 watches in the auction, Phillips and Sothebys selling for the same amount and Christies for CHF550 less.

The catalog also has to flow, now this is only a personal opinion but if I had a lot that might have trouble selling, then I would try and put it between two lots that should sell so there wasn’t a run of unsold items. Similarly you could also put it after a lot that you knew would sell really well as the room would be taking about it while you quietly passed the lot. Personally, ideally, if I had a really big lot that you wanted to do well, don’t put difficult sellers in the preceding lots as phone bidders will usually call the client 5 lots prior to make sure they are ready, if those 5 lots, or even part of those lots don’t sell, it can make an inexperienced bidder nervous the market has changed and they might not bid as strongly as they intended. We were always told if a phone bidder asks how the sale is going, say it’s going well.

Screenshot from Sotheby’s first three lots offered in their November 2023 Geneva auction, the first lot failed to sell and the second hammered below the estimate, making the auctioneer clearly nervous; the third, I’ll confess, did really well. As expected it would.

The auctioneer also has a responsibility and can greatly affect the outcome of a sale; from first hand experience I can tell you, often when you’re watching an auction and a certain lot seems to take ages to sell as the auctioneer is waiting for a response from a phone bidder, as the auctioneer, who’s role it is to get the highest price, time moves much faster. Similarly for the employee on the phone and bidder themselves, its rarely just someone sitting thinking ‘should I bid?’ Its more like currency calculations, questions about condition etc that take the time. One instance that comes to mind where an auctioneer changed the outcome was a very, very rare slip by Mr Bacs and possibly the only one I have ever seen him do. He was selling the Marlon Brando GMT in New York. Here, for me, he should never have let Alex Ghotbi bid in such small increments while Nathalie Maboron was bidding in sensible figures making the process take a crazy 20 minutes and most likely frustrate Nathalie’s client.

It’s probably also worth pointing out here that the auctioneer can ‘bounce’ bids up to the reserve, that means if the reserve is say $20,000 they can start at $10,000 and create fictional bids in the room until $19,000, but no higher. One of the best examples of this in action was while working at Bonhams, one of the last lots in the sale, with no absentee bids (bids left pre-auction) and only one person in the room, I had the only phone bidder. The auctioneer, as he opened the lot, looked at me then started very low taking fast consecutive ‘bounced’ bids that I relayed to my bidder, each time my bidder would shout to me “bid”, of course, he had already missed it, until the reserve, at that point when I asked him if he wanted to bid and he shouted yes and put my hand up, the auctioneer took my bid and the watch sold, a little smirk at his genius cunning appearing on the auctioneers face and a very bewildered sole participant in the room wondering who the other bidders were. This is also how auctioneers try to catch you out that the sale isn’t going well. By bouncing non-existent bids, which again is perfectly legal, until they reach just under the reserve hoping someone will jump in, if no-one does, they pass the lot, only, they don’t then have to say the lot is passed. If the sale is going well then often they will, otherwise “Down it goes” , “Same as the last” are popular comments. From memory in America, or certainly New York, where you need an auctioneer’s license prior, the rules state you can’t strike the gavel on a passed lot, however I note in other places they do strike the gavel. What you can’t say, although during the May Geneva auctions the Sotheby’s auctioneer was saying, is “Sold!” when a lot is passed. The trick here for the curious trying to work out what is sold and what isn’t, and remember the auctioneer will often try to fool you, and many are brilliant at it, is to listen for a paddle number, if no paddle number is called out, no sale. No matter what the auctioneer says otherwise.

Video of Aurel selling the famous Maron Brando Rolex GMT in New York, 2019. Usually, the auction increments should increase by 10 percent each time, so at a million dollars, the bid should increase by $100,000, not $10,000. A very rare error in my opinion.

This brings us to the famous paddle 1013 from Christie’s Geneva in November 2023, the paddle that bought most of the sale and I personally speculated was Christie’s protecting themselves from a guarantee provided to the seller (where the auction house guarantees the seller a set amount for this collection). According to Christies, they received a guarantee form a third party, paddle 1013, and so had to change all the reserves to reflect that guaranteed figure. A bit like someone leaving an absentee bid on the entire sale. To give an example though, the pre-sale printed low estimate for the collection was CHF19,305,000. The revised reserve, apparently based on the third parties guarantee, was a whopping CHF29,204,500.

The curious thing here though, for me, was, well, two things. Firstly, the auctioneer, who is insanely experienced, kept changing how he would call out paddle 1013 from English to French and in varying ways. ‘SOLD, paddle ten thirteen”, then “SOLD, paddle one thousand and thirteen, then the same in French, then “SOLD, paddle one zero one three, then back to French. If this was a genuine and legit situation, why the cloak and dagger? Or why the troubled look on his face? I’ve seen Christie’s auctions where one person, Saudi Royalty, bought a significant portion of the watch sale and no-one tried to hide his paddle number. The next thing from this sale, which brings more questions than answers; was the famous Marlon Brando GMT, again offered publicly after selling in New York in 2019 for US$1.95 million, the new reserve, as apparently put in place by the mysterious last minute guarantor, was an insane CHF3,750,000. If Christie’s explanation was correct, then this meant the guarantor had left an absentee bid of 3.75m for the lot and as per every other lot, if no-one bid higher, the guarantor, again paddle 1013, bought it. Only, for the ex-Brando GMT, the underbidder at 3.7m was in the front row and the winning bid of CHF3,750,000, the same as the reserve and guarantors absentee bid, was on the phone (keep in mind absentee bids always take priority over live bids.) So, well, what? How? Something was amiss as that contradicts the story Christie’s told Hodinkee post auction.

Christie's infamous paddle 1013 at it again, noticed how the auctioneer takes the bidding to CHF160,000 looking for 170k, then moves up to 165k before the paddle comes down. Of course, the sale was 100% sold but results should be dismissed.

Keeping with auction shenanigans, I recall years ago how Aurel at Christie’s was immensely proud and frequently used in PR how every sale had above 90 percent of the lots sold. A notable achievement. Although I haven’t read about it in the same way, Phillips maintains a similar figure. You know how he did that? Pre-sale, by looking at the absentee bids and phone bids booked, you can have a pretty good idea of how the sale is going to go. At that time, in the 2010’s, you wanted to stand on that podium for lot number one with around 50 percent of the sale already sold via absentee bids, today, it’s probably more like 70 percent not including phone bidders. So if Aurel has a watch that didn’t receive much interest or the consignor won’t lower the reserve to meet a low absentee bid, he withdraws it from the sale. That means, when auction stats are calculated, as the lot was withdrawn rather than passed, it doesn’t count and his high-sell rate maintained. Sounds shady? Not at all, just maybe, sneaky. He’s been doing it for decades though with no objections. I recall sitting in a Christies New York auction during the 2009 difficult years when the first session didn’t go well, then in the second session the auctioneer announced a number of lots were withdrawn, all the top lots in fact, mostly likely either as they belonged to one seller who got nervous, or Christie’s were concerned they wouldn’t sell so removed them. It’s a funny business this.

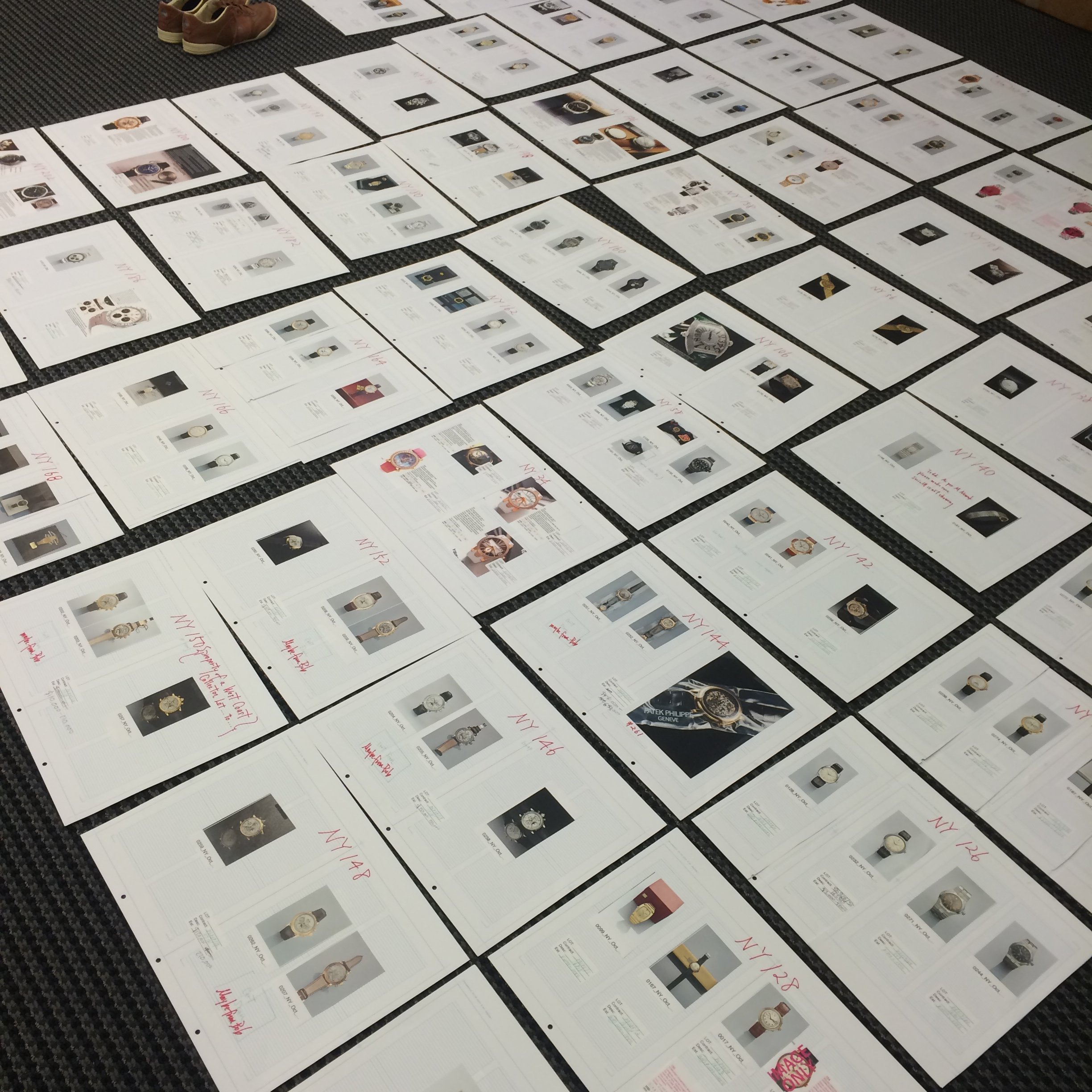

Working out the flow of an auction catalog the old fashioned way; shoes off, everything on the floor laid out for you to visualise.

Finally, a story. I’ll try to make it quick. While at Bonhams in 2007, I received a CD with various pictures on it, one of those was a Rolex triple calendar in steel, a reference 8171. These are rare and I really wanted it so immediately called the sender to discuss, who told me he had sent the same disc to Sotheby’s and Christies and would I please post him a proposal. I wrote one up for the whole collection with an estimate for the 8171 of US$30,000-50,000, which was the standard estimate at the time. Putting my letter in the outgoing mail, after I returned to my office and stared at my computer screen, zooming into the image of the 8171, transfixed, I just couldn’t believe it was genuine, the condition too good, but it looked genuine. Thinking then, wait, if it is this good and correct, it’s unlike anything we’ve seen before. I ran back to the mailroom, retrieved my letter, tore it up and sent another with a $50,000-70,000 estimate. Sure enough both my competition had used the market excepted $30-50k estimate and I won the contract. I was so happy I promptly drove to Las Vegas, without security, to a trade show in order to drum-up interest (pre instagram days!) And showed the watch to known VIP dealers who might bid on it. This was a mistake. Firstly, soon random people I didn’t know were asking to see the watch, then one dealer, the biggest of them all (an Italian) told me too many people knew I had the watch on my person and it was no longer safe for me. I left immediately, fast, running in fact. Secondly, and this brings us back to the auctions. There is a thing called ‘ringing’ in auctions, it’s illegal as it used to happen a lot in the early days, basically, you call everyone who you think will bid on the lot and you agree, pre-auction, a price between you, then one of you bids instead of you all bidding against each other and each pays out the other to avoid higher auction fees. When my spectacular Rolex 8171 came up for sale, all the big guys who had lusted after it had changed their mind, all of them, leaving only one who said he would bid but only within the estimate as he didn’t really want it anymore. Luckily, a client outside the known collective ring was bidding and so it sold for an impressive US$200,000.

Sometimes, albeit rarely, not everything that seems to good to be true, is. Exceptional Rolex Ref.8171 on its original felt strap with original buckle sold by Bonhams in 2007 hasn’t reappeared. Photo credit Bonhams auctioneers.

Why I Believe Rolex Bought Paul Newman’s Rolex Daytona ‘Paul Newman’

In the 1990’s Patek Philippe made no secret they would bid at auction, usually successfully, on their own historically important vintage watches in an effort to build inventory for the (2001) ’Patek Philippe Museum’ in Geneva. The fact that they had such deep pockets and knew the history of each watch, meant they usually bid a hefty premium and made the news as vintage watch prices started to seriously escalate. At that time, virtually every top lot reported at auction, almost without exception, was a Patek Philippe. You just can’t buy that sort of reputation and it secured them as the worlds foremost respected watch manufacturer, but, well, you can, obviously, buy that sort of reputation. In later years Omega started buying back their own watches at auction to build a museum, even going as far as to assist in the highly publicised Antiquorum OmegaMania auction in 2004. While Patek Philippe were usually publicly quoted as being the buyer of significant watches, Omega were less forthcoming about their participation. That said, Omega has every right to bid and buy at auction and no doubt still does, regardless though, they won’t buy just anything, only significant pieces they would put into their own museum.

This accepted and known practice of prestigious Swiss manufacturers bidding for their own vintage and highly collectible watches at auction didn’t muddy the waters, other than perhaps to dissuade some collectors from bidding when they assumed they would be against Patek Philippe, as they simply knew they wouldn’t win. Everything changed though when a French journalist for the Wall Street Journal, Stacy Meichtry, published an article in 2007 titled ‘How Top Watchmakers Intervene in Auctions’. The article suggested that manufacturers were buying back their own watches to artificially inflate prices and create demand. The article is one of the worse pieces of watch journalism I have ever read and so factually incorrect regarding both the manufacturers participation and the auction process, it’s amazing the WSJ ever published it, or weren’t sued. Even the title was incorrectly written. Amazingly, it’s still available online (https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB119178753176051433) Overall, the participation of watch manufacturers bidding at auction was written in a very scandalous way, and, well, the Swiss really don’t like scandals. It didn’t mention Patek Philippe also bid and bought watches from other makers it wanted for it’s museum and made it sound, at least to the average reader, like they were in cahoots with Antiquorum to bid on every Patek at auction and fool collectors by driving up prices, which was a lie. To the casual reader it was a bombshell and changed the way manufacturers bid at auction. Ever since the publication Patek Philippe stopped allowing the auction houses to announce their purchases to the press, initially changing the wording to “purchased by a private museum’ and then to simply requesting privacy. The same for Omega, Stacy Meichtry turned what was once an accepted and acknowledged practice of transparency, into secrecy. Which brings us to Rolex S.A.

The above images are the first ones James Cox emailed to me after almost 8 years of discussion regarding the history of the watch and establishing its unquestionable provenance. Note the discolouration to the dial, most likely from water damage.

Rolex are known to be perhaps the most secretive of Swiss watch companies, for good reason. When the founder of Rolex, Hans Wilsdorf died in 1960 with no heirs, he left his 100% ownership shares to the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation (founded in 1945). This means the profits from Rolex are re-invested back into the company and they’re not obliged to release financial details, it’s also why they spend more money on advertising the any other watch company, something like US$90 million annually and donate an unknown figure to numerous worthwhile events and charities. With an estimated US$10.7 billion value, Rolex really is unlike any other watch company. Ever noticed you never see a Rolex advert on the inner pages of a glossy magazine, only on the back or inner covers? When you spend the most, you demand the most. It’s well known within the industry Rolex have been quietly bidding and buying at auction for some time and purchase rare examples from select dealers; but it’s always very quietly. It’s also rumoured they’ve been acquiring watches with strong provenance. Which is why, in New York on October 26, 2017, when (ex) Phillips Geneva representative Dr Nathalie Monbaron bid $15.5 million (US$17.8 million with auction fees) for the Rolex Daytona ‘Paul Newman’ given to Paul Newman by his wife Joanne Woodward, I knew, with some decree of confidence, Rolex had bought it. The final two phone bidders were Nathalie Monbaron from Geneva and Tiffany To, from (previously) Hong Kong. Tiffany’s bidder, who we now know to be a Singapore collector, placed an opening bid of $10 million to take the room, and auctioneer, by surprise, however he was more cautious bidding in later stages raising the bid slowly in $100,000 increments. Nathalie on the other hand, speaking in French to her successful client on the phone, was bidding in a very prompt and precise manner, you could say, in a very Swiss way. The final bids were NB at 15 million, TT at 15.1 million and eventually NB at 15.5 million. Before Aurel Bacs put the gavel down he commented “It’s not going come back to you Tiffany, EVER, I know where it’s going’. This was an unusual and telling comment from Aurel as any collector could be tempted to sell, or his heirs have no interest in watches and sell, only if someone with no financial restrictions and a strong incentive to retain the watch would that comment be applicable, like a corporate company for instance. I heard stories subsequently about a Saudi Prince buying it, or Ralph Lauren, the latter I know untrue as the watch was offered directly to Ralph by (seller) James Cox (James asked me how much to ask, luckily, for him, I talked him out of selling) there were other similar unrealistic tales about the buyer, Ellen DeGeneres name was also bounced around; however sometimes this business is about reading between the lines.

The above image provides a link the actual auction on YouTube, note the methodic bidding from Nathalie

In late 2018 Rolex released the new website rolex.org to (finally) focus on their heritage and previous important owners. The Rolex advertising campaign stresses ‘Every Watch Tells a Story’ and, although it can always be argued Rolex watches have some pretty impressive owners, including dictators and presidents, none come to mind like the passion and influence Paul Newman impressed on the world when he wore his ref.6239 Daytona; a watch he gave away in 1986 because he jumped into a swimming pool with it on, forgetting it wasn’t waterproof and the glass steamed up. Yes, that was the original story James Cox told me about when Paul Newman gave it to him. Wouldn’t have made for a good press release though.

I would expect to see Rolex, finally, hopefully, open a museum in Geneva hosting their own watches and others, such as the first automatic watches launched by Harwood in 1926 that Rolex purchased the patent for in 1929 and released their own, improved, version of in the form of the Oyster Perpetual in 1931. Assuming they do open a museum, among the watches on display I am confident with be Paul Newman’s very own Rolex ‘Paul Newman’ alongside his ref.6263 ‘Drive Slowly’ and ref.116519 ‘Drive Very Slowly’ presumably given to Mr Newman by his wife on their 50th (golden) anniversary shortly before he died in 2008.

Of course, others will have a different view of the unknown buyer, or comment that they ‘know’ who the buyer was and it is a Saudi Prince, especially since Aurel Bacs commented in an interview the buyer was an individual, but knowing Aurel, that was a ruse to confuse. Of course one of the problems with this business is; everyone’s an expert.

Charles Tearle

The Rolex Submariner issued to the British military in the 1970’s, so called MilSub today, holds a special place among vintage Rolex collectors, or really, watch collectors in general. This is watch that to the untrained eye appears like a regular 5513 and most people won’t give it a second look, but those that know vintage watches, those that share your passion for it, they will know. Once part of the Special Forces diving gear, the Rolex Military Submariner could be considered the holy-grail of the Submariner model.

In the very early 1970’s the British Ministry of Defence (MOD) approached Rolex S.A (Geneva) to modify a Submariner non-date model reference 5513 for issue to the Royal Nay’s division of underwater soldiers known as The Special Boat Squadron. Their request included very specific requirements;

It must have hacking (stopping) seconds when the crown is pulled out to be able to synchronise watches at the start of a mission

A rotating bezel with full 60 minutes indicated with minute markers (instead of the civilian 15 minutes)

Gladiator hands providing greater legibility at night

Fixed strap bars to prevent potential spring-bar failure; this also means it could only be worn on an extendable NATO style or single pass-through strap.

Antireflective satin finish case

Encircled T confirming the luminous material used was Tritium (not Radium)

Although probably not an MOD request, the full serial number is engraved on the inside of the case back.

The left image shows an early 1970’s Ref.5513 MilSub with typical dial, the right image is a late 1970’s Ref.5517 MilSub with a more elongated coronet and larger lume-plots (maxi) dial typical of the era.

All of the above requirements were undertaken by Rolex Geneva with the delivered watches then engraved by the MOD in England, with relevant issue number and deployment details; this information was noted prior to issue. As the MilSubs were issued prior to a mission, regularly damaged in use and returned for servicing, the Gladiator hands and 60 minute bezels were regularly changed with civilian (Mercedes hands and 15-minute bezels), additionally, the casebooks regularly appear switched with other examples so the inner serial number doesn’t match the case serial. Whether this was by accident while being serviced, or by request so a serving issued watch couldn’t be traced, we don’t know. Regardless, today, a MilSub that has survived in original condition with correct matching case back is referred to as a ‘Full-Spec’ example. For those that have seen a full-spec mil-sub, or read about one, here’s a quick explanation of the reverse engravings. MilSubs issued to the SBS feature a ‘0552’ number special to British Navy Personnel, followed by /923-7697 used to designate it was a British divers watch. This number (0552/923-9697) doesn’t change for all watches issued to the British Navy. In addition, the case back is also engraved with a Broad Arrow, used to indicate the watch is property of the British military, finally followed by the individual issue number and year. Although today rare to see, late 1970’s examples were also issued to the British Army and instead feature a ‘W10’ code on the reverse with relevant army reference. Number for small issued item. (W10/6645-99-9237697)

After the initial batch of modified Ref.5513 Submariners were delivered, the second batch were due to have their own unique reference 5517 designation, however apparently the cases weren’t ready in time and so the delivery featured 5513 stamped between the shoulders and 5517 stamped to the underside of the lug. This dual 5513/5517 reference can be referred to by collectors as a 5515. The final batch delivered in the late 1970’s are stamped with the unique reference 5517 between the shoulders, they can also feature so-called maxi dials with larger luminous plots in keeping with regular production Submariner dials of the period.

POSITIONAL ERROR

While on one of my usual visits to a luxury modern watch store in London, while perusing the current offerings I overheard a customer saying to the salesperson he had heard it made a difference to the accuracy of his watch depending on which way he left it at night; crown up, or crown down, flat etc. The salesperson replied this wasn’t true as all the watches were tested in numerous positions on a machine before leaving the factory. I’ll admit, I think I might have let out a cough but restrained myself from calling the salespersons reply BS.

What the customer was referring to is positional error; this effects virtually all mechanical watches that use a balance spring, the exceptions being a tourbillon, although to completely remove positional error would take a gyro-tourbillon that rotated on two axis. When watches are tested for timekeeping by watchmakers it’s done on a machine that rotates them on both axis and an average is used. As we don’t move our wrist though the same movements, errors can occur. In theory, the same watch worn by someone who sits at a desk all day and leaves the watch crown up on its side at night, would have a difference accuracy if that person went on holiday, swam, played tennis, and remained active all day then left the watch crown down at night. Temperature can also affect timekeeping, thats why when you open a vintage Patek Philippe the movement is engraved ‘timed to heat, cold, isochronism and five positions’.

So the next time you go into a luxury watch store and ask a questions, please don’t expect you’ve received the correct answer.